Photographic Framing of Life

Using my own relationships with photography to figure out why I became who I am

My name is Charles Darr, and I go by Charles, Chuck, Uncle Chuck, and Chardarr. Here is a photo of me at 18 months old, trying to take photos at the zoo with my mother’s camera.

I am a photographer, a social enterprise strategist & communications specialist, and an artist.

I’m joining Substack to have a place to deliberate and develop work outside of the drive-thru framework of social media that is built by the priorities of quick, cheap, and just satiating enough. Here I will share thoughts fuller than those that can be passed through the window of a rapidly moving, algorithmically driven feed.

I hope that some of you may find these ramblings interesting, but most of all I hope to use this place as a garden bed to nurture my own growth.

As Chris Smither sings in No Love Today, “...In the end no one will sell you what you need, You can’t buy it off the shelf, You got to grow it from the seed…”

Welcome to Photo Seeds.

This first post is one I have been working on for a long time, and it will likely be the longest post I ever share.

One of the many things that I appreciate about photography is that it can serve as a historical reference guide. I carefully store and sort all of my camera files chronologically, and I regularly spend time looking back through them.

This is the first time, however, that I will analyze my life through my relationships with photography from the beginning until the present, as a method of understanding who I am, how I got here, and where I would like to direct my future.

1: Photography and the childhood trauma of growing up poor

I grew up in a low-income household in the underserved neighborhood of Maryvale, located in west Phoenix, Arizona. The families in my community did not have enough money to make ends meet. I had some friends whose parents would prioritize cable television and aftermarket auto accessories, but sometimes when you’d visit their house they wouldn’t have food or even toilet paper. The only time I remember asking my parents about our financial situation as a kid, they told me we were “middle class.” I learned later that they had routinely scraped coins to buy baby formula.

In these circumstances, when children ask about things that are introduced to them through commercials or more privileged kids, be it a toy or name brand shoes, most adults tend to scoff and say something like, “What?? No, we can’t have that, that’s not for us, that's for rich people!” This was a refrain sung by a chorus of school teachers, babysitters, friends’ parents… everyone but my parents, it seemed, made sure to let all the kids in the community know that they were poor, and therefore couldn’t have most things.

My response to this social conditioning was to remove my desire for the things that I feared would not be available to me. These included material possessions, academic and career aspirations, crushes, and in general, hopes and dreams of actualizing my potential in life. I simply accepted that the things worth having in life existed up in the atmosphere where only people flying at a higher altitude could access them. This way, I could take agency over my condition and mitigate the disappointment of not being worthy.

Despite the expectations for a low quality of life that are pervasive throughout communities in poverty, I was blessed to have parents who worked hard and spent judiciously. While I envied my friends who had occasional new possessions to show off, I benefited from my parents’ prioritization of an annual summer vacation instead. Each year we would pack ourselves (sometimes literally) into an ‘81 Ford Fairmont, and later an ‘89 Ford Taurus, and we would hit the road. Every year as we pulled out of the driveway my father would exclaim, “We. Are. On. Vaa-catiooooon!!”

These trips would prove to ignite my passion for photography. My mother always had a camera, but film has never been cheap, and so it was only during these special memory-worthy occasions that we would splurge and I would be able to shoot several rolls over the course of the week.

If “take what you can get” is the modus operandi of the poor, then photography gave me a method for trying to take as much as possible.

I never slept as we drove from state to state. To my sister’s chagrin, I would energize myself with singing, humming, or just making obnoxious sounds in order to keep my eyes open. I distinctly remember wanting light to reflect off as much of the planet and into my eyes as possible. I understood that there would never be another chance to experience those exact sights, at those exact moments in time, ever again.

The place we traveled to the most, of course, was Grandma’s house in the Ozarks of southern Missouri. Within a short drive of her house in West Plains were countless fresh water springs, watermills, creeks, caverns, railroad museums, parks, and other attractions. The excitement of getting to photograph all of these places that were exotic to a boy from the Sonoran Desert was one privilege, but getting to have and hold the prints later was another!

We couldn’t get all the rolls developed at once when we got back home, instead we would spread them out over pay periods. It seemed like a long time would pass before we would get to see the pictures and I wouldn’t remember what to expect when they were finally revealed.

After they were developed and printed out, the envelopes of photographs would go into a large chest in the living room, and I would spend a lot of time sitting on the floor, looking through each of them like listening to favorite albums over and over.

This was my first relationship with photography — It was a way of maximizing my yield in the take-what-you-can-get mindset that I had developed. Many things in life felt out of reach, but photography, I discovered, was a cheat code for hoarding life itself.

One year my uncle, Greg, gifted us a photo of a watermill from the Ozarks. I remember saying it looked like one of the places we had visited the last time we came to Missouri. Uncle Greg replied, “That's your picture!!” I couldn’t believe it. I had always loved photography, but I had never imagined that I could be an “actual” photographer. Simply seeing a decent quality print of one of my photos matted and framed changed my relationship with photography by elevating one of my pictures to that ascendent realm that I had assumed was not attainable.

2: High school yearbook editor turns college dropout

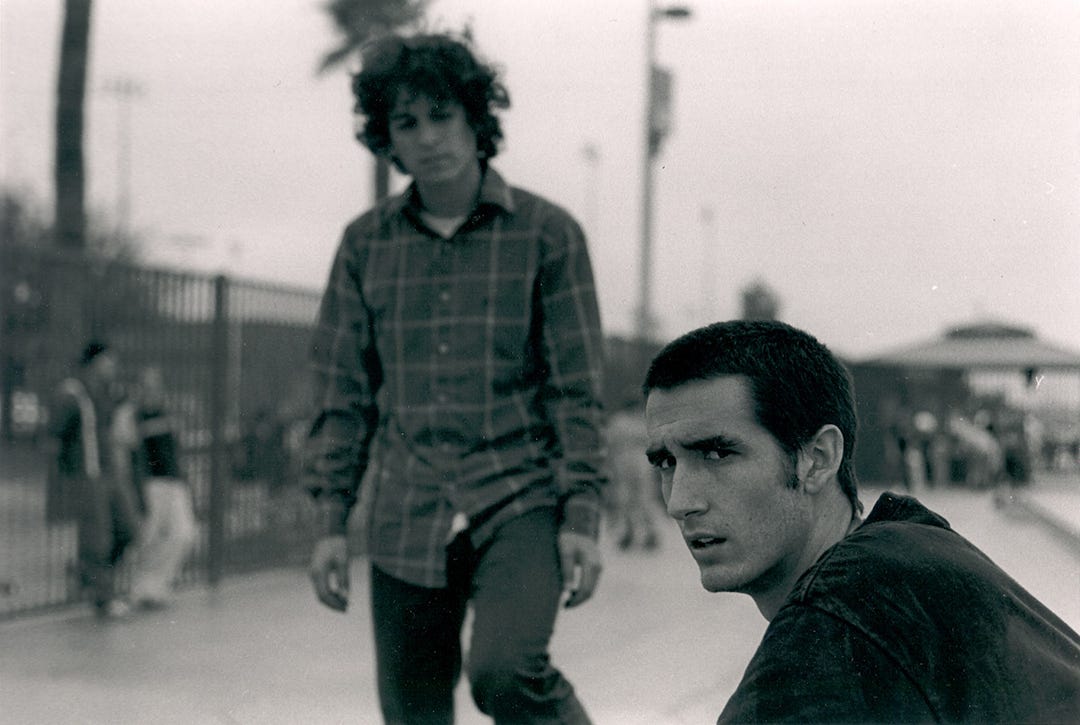

By high school I wanted to become my own person, and as is the case for so many boys, I thought this meant distancing myself from my parents. We still went on a couple family vacations, but it was during these years that my little sister was born and my big sister graduated and moved away for college. On top of that, I had become a skateboarder and as we traveled I spent less time shooting photos and more time searching for new spots to skate on my own.

In my senior year, though, I enrolled in our school’s yearbook class and became editor-in-chief. As it would turn out, most of the students who signed up for this class did so because they (correctly) assumed that they could get by without doing much of anything. Our cohort’s dearth of effort left plenty of opportunity for me to become the primary photographer as well. The school provided the first single lens reflex camera I ever got to use, as well as a supply of film that they would have developed.

While not producing any photographs of note, this experience strongly reinforced the idea that my Uncle Greg had helped spark that maybe I am a photographer.

After graduation from high school, I enrolled at ASU with the expectation that I would earn my degree in engineering. I was a little bit interested in materials and mechanical engineering, but I was not passionate about the idea of becoming an engineer for the rest of my life. As an elective I enrolled in a Photo 1 class that was taught by then graduate student, Michael Lundgren.

Concurrently, I began to hit a nadir in my life that had been developing for years, and I was diagnosed with depression. I felt lost, isolated, and had a difficult time imagining that my life would ever have value. The only refuge from the barrage of negative thoughts that made me question whether or not I’d be better off dead, was the darkroom.

I spent nearly every open lab hour buried in the basement of the art building, watching while images I had created manifested like magic on sheets of paper as I agitated them in the developer tray. The real world, the one that I was not made for and not compatible with, did not exist during those hours. I had discovered a portal into a parallel dimension in which I felt a sense of belonging.

Consequently, I spent so much time in the darkroom that I neglected to attend most of my other classes, and didn’t do much of the work for the ones that I aimlessly showed up for. I still didn’t know what I wanted out of life, but I knew that I no longer wanted to become an engineer. I told Lundgren that I wanted to do what he does, and he replied, “Well anyone can do what I do. I just go out and I make pictures.”

It was well beyond the course withdrawal deadline at that point of the semester so I just stopped going to my classes and failed out of college.

3: Photography & Ferality

As a young adult now living for the first time outside of the security of my parents’ home or a college campus, I did what I knew best — I took what I could get. As a result, I bounced around low paying thankless jobs, and I rented rooms from friends and acquaintances in some rather insalubrious situations.

Drunken neighbors set one apartment on fire as we slept inside during the early hours of the morning. Another room I rented was in a house that was a hangout for crack and heroin users/merchants before the shoddy roof caved in over my bed one night during a monsoon storm.

Through these distractions, I stayed focused on my aspiration to become a photographer. This effort was assisted by the fact that I began using cannabis daily. I found that for my type of depression and anxiety, cannabis helped me stay on track. It muted both intrinsic and extrinsic negative signals, it minimized my drinking, and it also served as a supplement for instant gratitude.

Maybe most importantly, using cannabis enabled me to forget that I didn’t know how to make good pictures, a problem that had stymied my efforts before, and it allowed me to get swept away in the discovery process of learning what works and what doesn’t. Skateboarding gave me lots of opportunities to photograph friends, both skating and socializing, and I got to feel another sense of photographic accomplishment seeing some of my pictures featured on the sleeve of one of Cowtown Skateboards’ VHS releases.

During these years I also attended community college part-time in order to earn my associate’s degree and transfer back to ASU as a returning student on academic probation. This time, I would study photography.

4: Getting high on my own supply

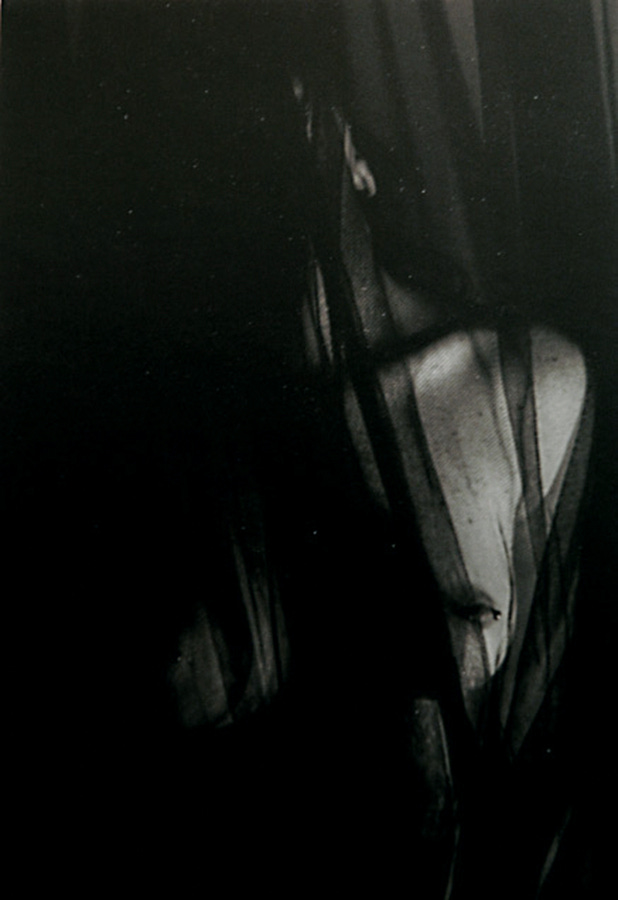

My first real project in photography school was a black and white portrait series. I clamped a work light inside a milkcrate and covered it with wax paper to build a softbox, then I invited friends to come to my apartment individually to sit for a photo shoot. I soon learned that, while supportive and willing to help, none of my friends were too excited to have their photo taken. I decided to begin each session by having them photograph me to break the ice.

As it turned out, this method obscured the roles of subject and object, and in doing so materialized, I believe, some hint of the nature of the connections I shared with my collaborators. This experiment would become the genesis of a persistent desire to try to photograph the psychic transmission of thoughts, a pivotal inspiration that would direct my photography not toward storytelling, per se, but more accurately, story suggesting.

I moved on from this bilateral strategy, while continuing to shoot portraits of friends. I was ready to break out of the pseudo studio that I had set up in my living room and see if I could capture the same authenticity out in the world.

Soon into my education, I fell in love with a particular notion of photography that I was learning, which Joel Eisinger coined “trace and transformation.” The concept addresses the unique capacity of photography amongst other artistic mediums to not only capture images from the physical world, but by confining those fleeting temporal moments into static photographic objects, photography renders them into derivative artifacts that then take on a separate life of their own.

As I became enamored with this new-to-me understanding of photography, a professor, Christian Widmer, provided an essay by Paul Graham called “The Unreasonable Apple” in which Graham eloquently describes this alchemical nature of the medium by revering photography as “the creative act when you dance with life itself - when you form the meaningless world into photographs, then form those photographs into a meaningful world.”

Simultaneously I was becoming a fan of the work of photographers like Nan Goldin and Dash Snow, who presented raw, emotion-saturated photographic records of their lives as compelling artist anthologies. While I immediately appreciated the authenticity of their images, I also suspected that the camera served as a kind of shield that they were using to protect themselves from their exposure to trauma. I believed that they were utilizing photography’s alchemy to temper the human experience in a way that offered an opportunity to diffuse the full brunt of the pain of life, while not forfeiting the life affirmations that come from living uninhibited. By transforming their chaotic worlds into art objects, they were living on the edge, while being able to dull it down just enough.

Also around this same point in my development, Andrew Hammerand, a fellow photography student and mentor gave me a book called “I Am Not This Body” by Barbara Ess, in which she writes, “The physical world itself so promising and comforting even in its damaged, crumbling, flooded, shining, decaying, pathetic state. We embrace its sweet dumbness in our craving to get at something real. Photography depends on light falling on or off this stuff and then pretends it’s the story. But I am not this body. But I am. This is not my story. But it is.”

While Ess seems to be addressing photographic alchemy from the other direction, that is, using photography to overcome an ethereal, dissociative state by creating material surrogates of validation, her passage also captures the duality that emerges when you center your lived experience as the subject of your photographic exploration. As you use photography to trace and verify your life, photographs will also transform your real life into a story of conjecture — one that may prove too seductive to avoid becoming captured by.

At this point in my life I was entirely detached from true human connection. A couple years prior I had met a woman with whom I quickly shared an overwhelming bond. I immediately felt as though that bond was the reason I was alive. She and I, so I believed, completed each other in a way that confirmed my existence’s meaning. However, that bond was soon broken and we stopped talking for a long period of time before eventually trying to reform our relationship as friends.

The heartache I experienced from that failed love was more than I ever wanted to feel, but at least it was over. For the first time in my life I had allowed myself to believe that something great — a fulfilling connection to being alive — had somehow slipped through the cracks of the upper, deserving tiers of society and landed in my lowly, unworthy path.

Once the cosmos corrected that error and took that connection back from me, I began replacing all of my pain with a yearning to have it returned. Paradoxically, I filled every ounce of my being with a longing so malignant that it would supplant any room for the love that it sought; but inversely, any room for pain that could be trafficked in with it. I had discovered that because my suffering was caused by a contrived longing, it was one that I could moderate, and thus tolerate, which was certainly a better alternative to the chance of another heartbreak.

So, as I learned about Nan Goldin and Dash Snow, and how one’s human experience can be the subject matter for their photographic exploration, I began to use photography as a dysfunctional method of processing my life and synthesizing art from it.

During a classroom critique of some of my “biographical” work, professor Betsy Schneider, a mentor whose pushback I respect and have benefited from, challenged me regarding the purpose of the work. I insisted that I was innately motivated by something I didn’t fully understand yet. She explained that if I’m not thinking about what I hope the work contributes to the field of art, then it’s not art, it’s art therapy. I said that’s fine, that I didn’t care how it would be categorized by outsiders because I was making the work for me, and if other people liked it then that would be a secondary benefit. Looking back, in a way, we were both right.

Fortunately for me as an aspiring artist, the type of despair apparent from a man who has shut himself off from the threat of emotions, and disguised his fear as a noble loyalty to his fateful anguish, happens to be the brand of misery that is magnetic.

Once I began attempting to photograph it, people were drawn to my condition, eager to try to decode it like a riddle. I was constantly called an enigma, and my morose, lamenting photographs were often exalted. I had fortuitously constructed a cinematic safe space for myself.

At the crescendo of my exhibitionist longing era, the ASU Student Photographers’ Association arranged an exhibition that would be open juried by the legendary photographer, Joel Meyerowitz. For my submission I offered some of my most recent work.

With all the student submissions laid out across tables in a conference room, Meyerowitz meandered the aisles, perusing the pictures while describing what he liked about the ones that caught his interest. When he reached my prints, Meyerowitz picked them up and showed them to everyone. Michael Lundgren, my longtime primary photography mentor and champion of photographic mysticism, stood by watching proudly as Meyerowitz said, “these pictures give me hope for the future of photography! There is something in them, there is a story, and they make me want to know more...”

And then I never made another photograph like those again.

The positive reinforcement that I received for both my persona and my photography quickly created a feedback loop. After only a few genuinely inquisitive weeks of trying to photograph my isolation, the photography tail began to wag the life dog. I soon leaned so far into playing the character birthed by my photographic creations that no number of conspicuous clothing hangers could remind me that I had the option to hang the costume up anytime I wanted. Like the Sabatier effect in a silver-gelatin print, the alchemy had reversed. Instead of creating a work of fiction derived from my life, my life had become a derivative of my work of fiction.

When this happened, photography became difficult. I was chasing the therapeutic effect of transmuting my suffering into a two-dimensional facsimile. But whatever authenticity that was woven into my pictures when I was converting my real, albeit indulgent misery into photographs was no longer there when the photographs began to motivate artificial misery.

Somehow, during this epoch of emotional unavailability, I ended up in the most secure and nourishing romantic relationship that I have ever been in, although I had trouble recognizing it at the time. The ability for the relationship to reach that level was likely bolstered by the fact that not only was I not taking it too seriously, but she had plans to move for grad school after finishing her degree, and those plans didn’t include dragging me along.

Yet, when it came time to break up, we learned that we had nonetheless developed strong feelings for one another and it was difficult for both of us to accept that it was over. It was easier for her, however, because she had been dating down, or “slumming it” with me, and someone with my edge to income ratio didn’t fit her life plan. In an effort to help me see the bright side she explained, “you don’t want this relationship, you’re an artist! You stopped making good photos when you were happy, you need the longing!”

That broke the spell for me. I no longer wanted to be the character in the story that my photography had created. I wanted to be happy and fulfilled and never again closed off to the possibility of creating a future with someone.

My whole subconscious conception of what it meant to be an art photographer was brought to the surface so fast that it succumbed to the bends. This dilemma was multiplied by the fact that my disabuse happened at the same time as I was finishing photography school. No more assignments, no more critiques, no more mentors, no more direction.

5: Who cares? (And what do they care about?)

In the decade-plus since finishing my undergraduate degree in photography, I have done many things, including work as a production assistant, a grip, and a cinematographer on a commercial, a television series, and a documentary, respectively, and I have provided professional photography for a number of clients. I earned my master’s degree in sustainability with a focus on social entrepreneurship, and I have helped clients with organizational development, communications strategies, and the production of outreach assets.

However, for the sake of this reflection, I will finish by focusing only on the personal interest projects that I’ve been working on, as the aforementioned roles are only germane to my relationship with photography insomuch as they are acknowledged.

Of the various ideas I have tinkered with in this time span, two have developed into projects.

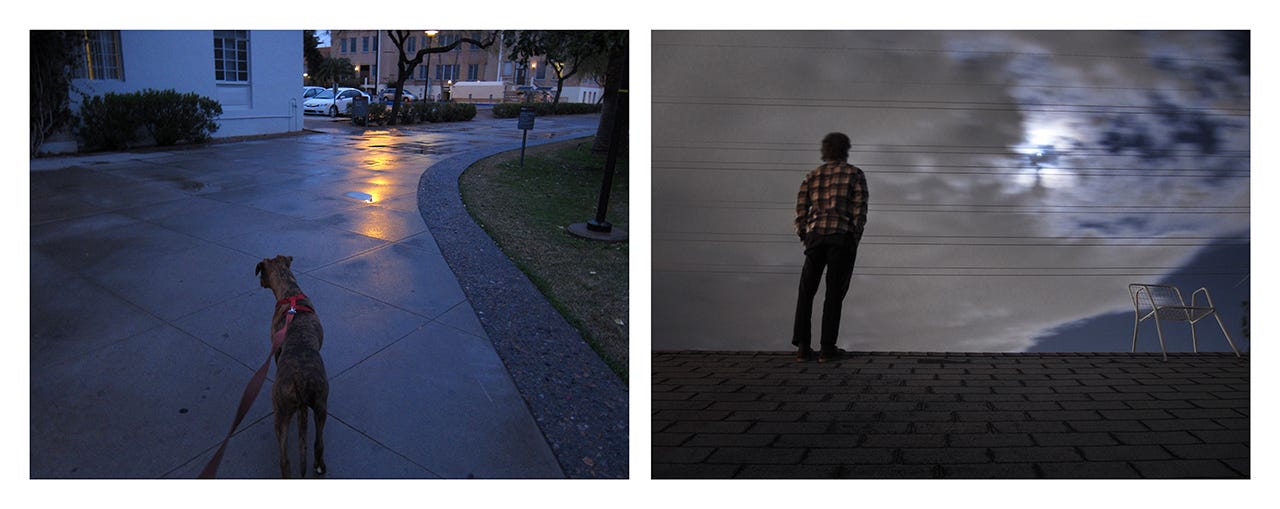

The first began shortly after abandoning my cloying self-centered work at the culmination of my photography degree. For whatever reasons, survey data show that a very large plurality of students who earn a degree in fine art photography stop making photographs soon after they graduate. And, I would wager, most do not endure the psychic melodrama related to their own photography that I subjected myself to. With pressure to not succumb to this Great Filter, I rewound to my initial interest from when I began the photo program — portrait photography.

I wanted to learn what made other artists pursue their passions. With all of the potential that being given a chance to be alive provides, with consciousness and bodies on brief loan to their souls from the heavens, what interests had others discovered that made them appreciate their gifts? In other words, what had other people found that made life worth living?

I began reaching out to friends who are driven by their life’s calling. Fortunately for me, I knew many musicians, painters, entrepreneurs, designers, builders, skateboarders, and other photographers. I came to these friends in their creative spaces. I wanted to photograph them inside their passion’s incubator in an effort to include bits and pieces of evidence in my pictures, clues as to what gave their life purpose. I aimed to suggest some story about their raison d’etre, like a documentary film in a single frame.

I shot these photos using a first-generation Sony RX100, an unassuming point-and-shoot pocket camera. The unique thing about this camera is that the on-camera flash pops up out of the top of the camera, and is equipped with a spring hinge that allows you to pull it back and tilt it upward. This way, you can bounce supplemental light off a ceiling and diffuse it over the entire scene, distributing enough exposure across the frame to provide sufficient data throughout the image to manipulate using local area adjustments in Photoshop, making it look as though it has been lit and shot with much higher quality equipment than one would assume could be achieved with a point-and-shoot camera.

While frugality was the entire decision making rubric when it came to gear, I discovered that using this tiny camera and not surrounding my friends with off-camera flashes on light stands helped create a more authentic shared experience between me and my subjects that felt less extractive than showing up and doing photography to them.

Each photograph would take thirty minutes to an hour to capture. I would explain that I was just going to start shooting some exposures to get my camera settings and framing dialed in the way that I wanted, and that that would take some time, so they shouldn’t worry about any of the initial shots because they were all throwaways. Then we would begin to chat and I would investigate their passion.

As we would talk about how they became interested in their preoccupations and their methods of pursuit, I would continue to rhythmically bounce my little flash off their ceiling until I hypnotized them into forgetting that they were having their photo taken. Never telling them that the practice shots had ended, the “warm-up process” would lull them into a state of comfort until the camera essentially no longer existed and it was just me and a friend sharing conversation.

Over the course of a few years, I would make these portraits of 65 friends. The project landed me a cover story in a local art publication called Java Magazine, and was also selected for a juried exhibition of self-published photo books at Phoenix Art Museum.

The second project is progeny to the first one. Having space to set up a photo studio at my home, I wanted to see if I could figure out how to replicate the same “cameraless” portrait strategy, but inside a studio setting complete with professional equipment consisting of lighting and a big loud camera.

I decided that strobe lighting would be too disorienting for intimate conversation, and too reorienting to the fact that we are actually doing a photoshoot. Instead I set up video lights that run continuously and don’t reveal when photos are being shot. I also didn’t want the camera to interfere with creating an environment that fosters feelings of safety and openness, so rather than holding it in front of my face I decided I would shoot with it mounted on a tripod using a cable release for the shutter, allowing me to make eye contact.

While this arrangement does not replicate the same natural environment that my previous project had benefited from, I have been able to utilize it well enough to get my volunteers to forget that we are shooting photos and focus all their attention instead on our one- to two-hour conversations with one another. Rather than using context clues to suggest their stories, I have begun to try to capture a similar suggestion in the eyes of my friends. The greatest feedback I have received in regards to this work came from my lifelong best friend, Mark Lawless, who told me, “I don’t know any of these people, but when I look at your pictures I feel like I’ve known them a lifetime.”

As may be apparent if you have read this far, my relationships with photography, and my life in general, seem to be fueled by a desperation to find or create meaning out of my existence. But I don’t think that’s quite right. I think I have been searching all along for opportunities to achieve what I’ve long believed to be my life’s meaning. As a young child I began contemplating why we are all here. Not in a material, biological way, but why does consciousness exist?

I can remember being about nine years old and, after really focusing on some if-then sequences as hard as a beginner brain is capable, I came to the conclusion that the only reason that makes any kind of sense to me is that we are straightforwardly here to experience being alive. Through the good, the bad, and the boring, surely we must be here to take in all the individual moments while struggling to remember to be aware of the singular lifelong experience.

(Most of my ability to articulate the conclusions of my nine-year-old self have developed in the years since.)

Specifically, I determined, the main feature of the show has to be our connections to one another. To explore relationships and share experiences, to compare insights and create bonds with other spirits during our tenure together as humans, for a brief time until we return to wherever we came from before we were born.

I think photography can offer a promising conduit to create such opportunities.

For the past few years I have increasingly outgrown my take-what-you-can-get self limiting disorder and have been pushing unapologetically toward living a more intentional life.

I am pleased with the photographs that my current project is producing, but I’m also restless to explore how it can be taken further, and to see what new project it will eventually procreate.

Most importantly, having an excuse to make time to connect with others brings me back to those first days in the darkroom with that same comforting assurance that at least in those hours, I am where I belong, and I am worthy.

Seriously good stuff here. I remember obsessing over the environmental portraiture work on Slap—really interesting to hear you contextualize it within your broader journey in photography. Stoked to keep reading!